Way back in the pre-pandemic era, when record-low unemployment was a top story on business pages, factory jobs languished unfilled as the industry struggled at least in part with a youth problem: how to grab the attention of valuable new college graduates.

These days, the industry has a new youth challenge – one that’s created by people who haven’t even started first grade.

According to the Wall Street Journal, the latest shortage to hit American factories comes in the form of child care, specifically parents who don’t have any. Schools and daycares are closed. Grandparent sitters are too much at risk of the virus to pitch in. Parents without the usual options have no choice but to stay home. And the costs are mighty. One factory saw absentee rates climbs as high as 50% -- staggeringly more than its typical rate of less than 10%. Another said child care has edged out worries about coronavirus as the top reason for calling out.

The snag shouldn’t be a surprise. Corporate offices may be wrangling with the eventual return to worksites. But factory workers never left. For them, being on site is the only way to be productive. Yet for someone with a small child and a factory job, the absence of child care is an insurmountable obstacle that ends the workday before it starts.

“You can’t leave a 6-year-old at home by themselves,” one HR leader told the Journal.

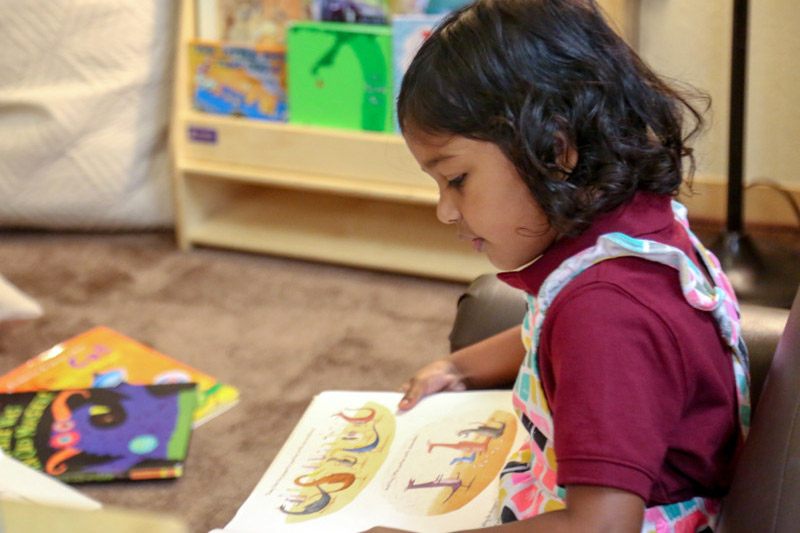

All this for an industry still battling technological overhaul and associated skills shortages, issues leaders have been scrambling for years to manage. It’s set off a wave of response strategies – from development tracks to tuition reimbursement. Now the lengthening list of line challenges also includes getting people to work, making it no surprise employers are adding child care to the roster of responses. Toyota Motor Corp is among US companies getting creative, telling WSJ they’re offering about 45 children a spot in a virtual-learning center at their Kentucky car plant. “The children use laptops to do schoolwork,” wrote the Journal, “while in-person teachers monitor their progress.”

The move mirrors employers both industry- and nationwide, all of whom are finding new ways to serve the school-age set. Tutoring discounts and help with forming learning pods are just two of the new benefits on which the Washington Post reported earlier this month. New programs continue to evolve.

For manufacturing, the innovations are well timed. In a pandemic era known for job losses, manufacturing is experiencing the opposite effect, with the Wall Street Journal reporting open manufacturing jobs in July returning to pre-pandemic levels. Reports in part blame child care shortages. “Toyota said this has helped workers show up,” reported WSJ. That same support has the fringe benefit of ensuring people are focused, too.

Said Myriah Sweeney to WSJ about the Toyota program she oversees: “They [parents] don’t need to stress about how their kids will do school.”